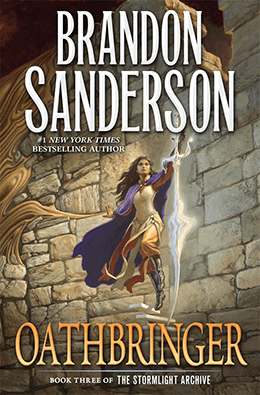

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 16

Wrapped Three Times

For in this comes the lesson.

—From Oathbringer, preface

A legend rested on the stone slab before Dalinar. A weapon pulled from the ancient mists of time, and said to have been forged during the shadowdays by the hand of God himself. The Blade of the Assassin in White, claimed by Kaladin Stormblessed during their clash above the storm.

Upon cursory inspection, it was indistinguishable from an ordinary Shardblade. Elegant, relatively small—in that it was barely five feet long— it was thin and curved like a tusk. It had patterns only at the base of the blade near the hilt.

He’d lit it with four diamond broams, placed at the corners of the altar-like stone slab. This small room had no strata or paintings on the walls, so the Stormlight lit only him and that alien Blade. It did have one oddity.

There was no gemstone.

Gemstones were what allowed men to bond to Shardblades. Often affixed at the pommel, though occasionally at the spot where hilt met blade, the gem would flash when you first touched it, initiating the process. Keep the Blade with you for a week, and the Blade became yours—dismissible and returnable in time with your heartbeat.

This Blade didn’t have one. Dalinar hesitantly reached out and rested his fingers on its silvery length. It was warm to the touch, like something alive.

“It doesn’t scream when I touch it,” he noted.

The knights, the Stormfather said in his head, broke their oaths. They abandoned everything they’d sworn, and in so doing killed their spren. Other Blades are the corpses of those spren, which is why they scream at your touch. This weapon, instead, was made directly from Honor’s soul, then given to the Heralds. It is also the mark of an oath, but a different type—and does not have the mind to scream on its own.

“And Shardplate?” Dalinar asked.

Related, but different, the Stormfather rumbled. You haven’t spoken the oaths required to know more.

“You cannot break oaths,” Dalinar said, fingers still resting on the Honorblade. “Right?”

I cannot.

“What of the thing we fight? Odium, the origin of the Voidbringers and their spren. Can he break oaths?”

No, the Stormfather said. He is far greater than I, but the power of ancient Adonalsium permeates him. And controls him. Odium is a force like pressure, gravitation, or the movement of time. These things cannot break their own rules. Nor can he.

Dalinar tapped the Honorblade. A fragment of Honor’s own soul, crystalized into metallic form. In a way, the death of their god gave him hope—for if Honor had fallen, surely Odium could as well.

In visions, Honor had left Dalinar with a task. Vex Odium, convince him that he can lose, and appoint a champion. He will take that chance instead of risking defeat again, as he has suffered so often. This is the best advice I can give you.

“I’ve seen that the enemy is preparing a champion,” Dalinar said. “A dark creature with red eyes and nine shadows. Will Honor’s suggestion work? Can I make Odium agree to a decisive contest between me and that champion?”

Of course Honor’s suggestion would work, the Stormfather said. He spoke it.

“I mean,” Dalinar said, “why would it work? Why would this Odium ever agree to a contest of champions? It seems too momentous a matter to risk on something so small and inferior as the prowess and will of men.”

Your enemy is not a man like you, the Stormfather replied, voice rumbling, thoughtful. Even… frightened. He does not age. He feels. He is angry. But this does not change, and his rage does not cool. Epochs can pass, and he will remain the same.

To fight directly might coax out forces that could hurt him, as he has been hurt before. Those scars do not heal. To pick a champion, then lose, will only cost him time. He has that in plenitude. He still will not agree easily, but it is possible he will agree. If presented with the option in the right moment, the right way. Then he will be bound.

“And we win…”

Time, the Stormfather said. Which, though dross to him, is the most valuable thing a man can have.

Dalinar slipped the Honorblade off the slab. At the side of the room, a shaft cut into the ground. Two feet wide, it was one of many strange holes, corridors, and hidden corners they’d found in the tower city. This one was probably part of a sewage system; judging by the rust on the edges of the hole, there had once been a metal pipe here connecting the stone hole in the floor to one in the ceiling.

One of Navani’s primary concerns was figuring out how all this worked. For now, they’d gotten by using wooden frames to turn certain large, communal rooms with ancient baths into privies. Once they had more Stormlight, their Soulcasters could deal with the waste, as they’d done in the warcamps.

Navani found the system inelegant. Communal privies with sometimes long lines made for an inefficient city, and she claimed that these tubes indicated a widespread piping and sanitation system. It was exactly the sort of large-scale civic project that engaged her—he’d never known anyone to get as excited by sewage as Navani Kholin.

For now, this tube was empty. Dalinar knelt and lowered the sword into the hole, sliding it into a stone sheath he’d cut in the side. The upper lip of the hole shielded the protruding hilt from sight; you’d have to reach down and feel in the hole to find the Honorblade.

He stood up, then gathered his spheres and made his way out. He hated leaving it there, but he could think of nothing safer. His rooms didn’t feel secure enough yet—he had no vault, and a crowd of guards would only draw attention. Beyond Kaladin, Navani, and the Stormfather himself, nobody even knew that Dalinar had this. If he masked his movements, there was virtually no chance of the Blade being discovered in this vacant portion of the tower.

What will you do with it? the Stormfather asked as Dalinar entered the empty corridors. It is a weapon beyond parallel. The gift of a god. With it, you would be a Windrunner unoathed. And more. More that men do not understand, and cannot. Like a Herald, nearly.

“All the more reason,” Dalinar said, “to think very carefully before using it. Though I wouldn’t mind if you kept an eye on it for me.”

The Stormfather actually laughed. You think I can see all things?

“I kind of assumed… The map we made…”

I see what is left out in the storms, and that darkly. I am no god, Dalinar Kholin. No more than your shadow on the wall is you.

Dalinar reached the steps downward, then wound around and around, holding a broam for light. If Captain Kaladin didn’t return soon, the Honorblade would provide another means of Windrunning—a way to get to Thaylen City or Azir at speed. Or to get Elhokar’s team to Kholinar. The Stormfather had also confirmed it could work Oathgates, which might prove handy.

Dalinar reached more inhabited sections of the tower, which bustled with movement. A chef’s assistants hauling supplies from the storage dump right inside the tower gates, a couple of men painting lines on the floor to guide, families of soldiers in a particularly wide hallway, sitting on boxes along the wall and watching children roll wooden spheres down a slope into a room that had probably been another bath.

Life. Such an odd place to make a home, yet they’d transformed the barren Shattered Plains into one. This tower wouldn’t be so diff rent, assuming they could keep farming operations going on the Shattered Plains. And assuming they had enough Stormlight to keep those Oathgates working.

He was the odd man out, holding a sphere. Guards patrolled with lanterns. The cooks worked by lamp oil, but their stores were starting to run low. The women watching children and darning socks used only the light of a few windows along the wall here.

Dalinar passed near his rooms. Today’s guards, spearmen from Bridge Thirteen, waited outside. He waved for them to follow him.

“Is all well, Brightlord?” one asked, catching up quickly. He spoke with a slow drawl—a Koron accent, from near the Sunmaker Mountains in central Alethkar.

“Fine,” Dalinar said tersely, trying to determine the time. How long had he spent speaking with the Stormfather?

“Good, good,” the guard said, spear held lightly to his shoulder. “Wouldn’t want anything ta have happened ta you. While you were out. Alone. In the corridors. When you said nobody should be going about alone.”

Dalinar eyed the man. Clean-shaven, he was a little pale for an Alethi and had dark brown hair. Dalinar vaguely thought the man had shown up among his guards several times during the last week or so. He liked to roll a sphere across his knuckles in what Dalinar found to be a distracting way.

“Your name?” Dalinar asked as they walked.

“Rial,” the man said. “Bridge Thirteen.” The soldier raised a hand and gave a precise salute, so careful it could have been given by one of Dalinar’s finest officers, except he maintained the same lazy expression.

“Well, Sergeant Rial, I was not alone,” Dalinar said. “Where did you get this habit of questioning officers?”

“It isn’t a habit if you only do it once, Brightlord.”

“And you’ve only ever done it once?”

“Ta you?”

“To anyone.”

“Well,” Rial said, “those don’t count, Brightlord. I’m a new man. Reborn in the bridge crews.”

Lovely. “Well, Rial, do you know what time it is? I have trouble telling in these storming corridors.”

“You could use the clock device Brightness Navani sent you, sir,” Rial said. “I think that’s what they’re for, you know.”

Dalinar affixed him with another glare.

“Wasn’t questioning you, sir,” Rial said. “It wasn’t a question, see.…”

Dalinar finally turned and stalked back down the corridor to his rooms. Where was that package Navani had given him? He found it on an end table, and from inside it removed a leather bracer somewhat like what an archer would wear. It had two clock faces set into the top. One showed the time with three hands—even seconds, as if that mattered. The other was a stormclock, which could be set to wind down to the next projected highstorm.

How did they get it all so small? he wondered, shaking the device. Set into the leather, it also had a painrial—a gemstone fabrial that would take pain from him if he pressed his hand on it. Navani had been working on various forms of pain-related fabrials for use by surgeons, and had mentioned using him as a test subject.

He strapped the device to his forearm, right above the wrist. It felt conspicuous there, wrapping around the outside of his uniform sleeve, but it had been a gift. In any case, he had an hour until his next scheduled meeting. Time to work out some of his restless energy. He collected his two guards, then made his way down a level to one of the larger chambers near where he housed his soldiers.

The room had black and grey strata on the walls, and was filled with men training. They all wore Kholin blue, even if just an armband. For now both lighteyes and dark practiced in the same chamber, sparring in rings with padded cloth mats.

As always, the sounds and smells of sparring warmed Dalinar. Sweeter than the scent of flatbread baking was that of oiled leather. More welcoming than the sound of flutes was that of practice swords rapping against one another. Wherever he was, and whatever station he obtained, a place like this would always be home.

He found the swordmasters assembled at the back wall, seated on cushions and supervising their students. Save for one notable exception, they all had squared beards, shaved heads, and simple, open-fronted robes that tied at the waist. Dalinar owned ardents who were experts in all manner of specialties, and per tradition any man or woman could come to them and be apprenticed in a new skill or trade. The swordmasters, however, were his pride.

Five of the six men rose and bowed to him. Dalinar turned to survey the room again. The smell of sweat, the clang of weapons. They were the signs of preparation. The world might be in chaos, but Alethkar prepared.

Not Alethkar, he thought. Urithiru. My kingdom. Storms, it was going to be diffi ult to accustom himself to that. He would always be Alethi, but once Elhokar’s proclamation came out, Alethkar would no longer be his. He still hadn’t figured out how to present that fact to his armies. He wanted to give Navani and her scribes time to work out the exact legalities.

“You’ve done well here,” Dalinar said to Kelerand, one of the swordmasters. “Ask Ivis if she’d look at expanding the training quarters into adjacent chambers. I want you to keep the troops busy. I’m worried about them getting restless and starting more fights.”

“It will be done, Brightlord,” Kelerand said, bowing.

“I’d like a spar myself,” Dalinar said.

“I shall find someone suitable, Brightlord.”

“What about you, Kelerand?” Dalinar said. The swordmaster bested Dalinar two out of three times, and though Dalinar had given up delusions of someday becoming the better swordsman—he was a soldier, not a duelist—he liked the challenge.

“I will,” Kelerand said stiffly, “of course do as my highprince commands, though if given a choice, I shall pass. With all due respect, I don’t feel that I would make a suitable match for you today.”

Dalinar glanced toward the other standing swordmasters, who lowered their eyes. Swordmaster ardents weren’t generally like their more religious counterparts. They could be formal at times, but you could laugh with them. Usually.

They were still ardents though.

“Very well,” Dalinar said. “Find me someone to fight.”

Though he’d intended it only as a dismissal of Kelerand, the other four joined him, leaving Dalinar. He sighed, leaning back against the wall, and glanced to the side. One man still lounged on his cushion. He wore a scruffy beard and clothing that seemed an afterthought—not dirty, but ragged, belted with rope.

“Not offended by my presence, Zahel?” Dalinar asked.

“I’m offended by everyone’s presence. You’re no more revolting than the rest, Mister Highprince.”

Dalinar settled down on a stool to wait.

“You didn’t expect this?” Zahel said, sounding amused.

“No. I thought… well, they’re fighting ardents. Swordsmen. Soldiers, at heart.”

“You’re dangerously close to threatening them with a decision, Brightlord: choose between God and their highprince. The fact that they like you doesn’t make the decision easier, but more difficult.”

“Their discomfort will pass,” Dalinar said. “My marriage, though it seems dramatic now, will eventually be a mere trivial note in history.”

“Perhaps.”

“You disagree?”

“Every moment in our lives seems trivial,” Zahel said. “Most are forgotten while some, equally humble, become the points upon which history pivots. Like white on black.”

“White… on black?” Dalinar asked.

“Figure of speech. I don’t really care what you did, Highprince. Lighteyed self-indulgence or serious sacrilege, either way it doesn’t aff ct me. But there are those who are asking how far you’re going to end up straying.”

Dalinar grunted. Honestly, had he expected Zahel of all people to be helpful? He stood up and began to pace, annoyed at his own nervous energy. Before the ardents could return with someone for him to duel, he stalked back into the middle of the room, looking for soldiers he recognized. Men who wouldn’t feel inhibited sparring with a highprince.

He eventually located one of General Khal’s sons. Not the Shardbearer, Captain Halam Khal, but the next oldest son—a beefy man with a head that had always seemed a little too small for his body. He was stretching after some wrestling matches.

“Aratin,” Dalinar said. “You ever sparred with a highprince?”

The younger man turned, then immediately snapped to attention. “Sir?”

“No need for formality. I’m just looking for a match.”

“I’m not equipped for a proper duel, Brightlord,” he said. “Give me some time.”

“No need,” Dalinar said. “I’m fine for a wrestling match. It’s been too long.”

Some men would rather not spar with a man as important as Dalinar, for fear of hurting him. Khal had trained his sons better than that. The young man grinned, displaying a prominent gap in his teeth. “Fine with me, Brightlord. But I’ll have you know, I’ve not lost a match in months.”

“Good,” Dalinar said. “I need a challenge.”

The swordmasters finally returned as Dalinar, stripped to the waist, was pulling on a pair of sparring leggings over his undershorts. The tight leggings came down only to his knees. He nodded to the swordmasters— ignoring the gentlemanly lighteyes they’d sought out for him to spar—and stepped into the wrestling ring with Aratin Khal.

His guards gave the swordmasters a kind of apologetic shrug, then Rial counted off a start to the wrestling match. Dalinar immediately lunged forward and slammed into Khal, grabbing him under the arms, struggling to hold his feet back and force his opponent off balance. The wrestling match would eventually go to the ground, but you wanted to be the one who controlled when and how that happened.

There was no grabbing the leggings in a traditional vehah match, and of course no grabbing hair, so Dalinar twisted, trying to get his opponent into a sturdy hold while preventing the man from shoving Dalinar over. Dalinar scrambled, his muscles taut, his fingers slipping on his opponent’s skin.

For those frantic moments, he could focus only on the match. His strength against that of his opponent. Sliding his feet, twisting his weight, straining for purchase. There was a purity to the contest, a simplicity that he hadn’t experienced in what seemed like ages.

Aratin pulled Dalinar tight, then managed to twist, tripping Dalinar over his hip. They went to the mat, and Dalinar grunted, raising his arm to his neck to prevent a chokehold, turning his head. Old training prompted him to twist and writhe before the opponent could get a good grip on him.

Too slow. It had been years since he’d done this regularly. The other man moved with Dalinar’s twist, forgoing the attempt at a chokehold, instead getting Dalinar under the arms from behind and pressing him down, face against the mat, his weight on top of Dalinar.

Dalinar growled, and by instinct reached out for that extra reserve he’d always had. The pulse of the fight, the edge.

The Thrill. Soldiers spoke of it in the quiet of the night, over campfires. That battle rage unique to the Alethi. Some called it the power of their ancestors, others the true mindset of the soldier. It had driven the Sunmaker to glory. It was the open secret of Alethi success.

No. Dalinar stopped himself from reaching for it, but he needn’t have worried. He couldn’t remember feeling the Thrill in months—and the longer he’d been apart from it, the more he’d begun to recognize that there was something profoundly wrong about the Thrill.

So he gritted his teeth and struggled—cleanly and fairly—with his opponent.

And got pinned.

Aratin was younger, more practiced at this style of fight. Dalinar didn’t make it easy, but he was on the bottom, lacked leverage, and simply wasn’t as young as he’d once been. Aratin twisted him over, and before too long Dalinar found himself pressed to the mat, shoulders down, completely immobilized.

Dalinar knew he was beaten, but couldn’t bring himself to tap out. Instead he strained against the hold, teeth gritted and sweat pouring down the sides of his face. He became aware of something. Not the Thrill… but Stormlight in the pocket of his uniform trousers, lying beside the ring.

Aratin grunted, arms like steel. Dalinar smelled his own sweat, the rough cloth of the mat. His muscles protested the treatment.

He knew he could seize the Stormlight power, but his sense of fairness protested at the mere thought. Instead he arched his back, holding his breath and heaving with everything he had, then twisted, trying to get back on his face for the leverage to escape.

His opponent shifted. Then groaned, and Dalinar felt the man’s grip slipping… slowly.…

“Oh, for storm’s sake,” a feminine voice said. “Dalinar?”

Dalinar’s opponent let go immediately, backing away. Dalinar twisted, puffing from exertion, to find Navani standing outside the ring with arms folded. He grinned at her, then stood up and accepted a light takama over-shirt and towel from an aide. As Aratin Khal retreated, Dalinar raised a fist to him and bowed his head—a sign that Dalinar considered Aratin the victor. “Well played, son.”

“An honor, sir!”

Dalinar threw on the takama, turning to Navani and wiping his brow with the towel. “Come to watch me spar?”

“Yes, what every wife loves,” Navani said. “Seeing that in his spare time, her husband likes to roll around on the floor with half-naked, sweaty men.” She glanced at Aratin. “Shouldn’t you be sparring with men closer to your own age?”

“On the battlefield,” Dalinar said, “I don’t have the luxury of choosing the age of my opponent. Best to fight at a disadvantage here to prepare.” He hesitated, then said more softly, “I think I almost had him anyway.”

“Your definition of ‘almost’ is particularly ambitious, gemheart.”

Dalinar accepted a waterskin from an aide. Though Navani and her aides weren’t the only women in the room, the others were ardents. Navani in her bright yellow gown still stood out like a flower on a barren stone field.

As Dalinar scanned the chamber, he found that many of the ardents— not just the swordmasters—failed to meet his gaze. And there was Kadash, his former comrade-in-arms, speaking with the swordmasters.

Nearby, Aratin was receiving congratulations from his friends. Pinning the Blackthorn was considered quite the accomplishment. The young man accepted their praise with a grin, but he held his shoulder and winced when someone slapped him on the back.

I should have tapped out, Dalinar thought. Pushing the contest had endangered them both. He was annoyed at himself. He’d specifically chosen someone younger and stronger, then became a poor loser? Getting older was something he needed to accept, and he was kidding himself if he actually thought this would help him on the battlefield. He’d given away his armor, no longer carried a Shardblade. When exactly did he expect to be fighting in person again?

The man with nine shadows.

The water suddenly tasted stale in his mouth. He’d been expecting to fight the enemy’s champion himself, assuming he could even make the contest happen to their advantage. But wouldn’t assigning the duty to someone like Kaladin make far more sense?

“Well,” Navani said, “you might want to throw on a uniform. The Iriali queen is ready.”

“The meeting isn’t for a few hours.”

“She wants to do it now. Apparently, her court tidereader saw something in the waves that means an earlier meeting is better. She should be contacting us any minute.”

Storming Iriali. Still, they had an Oathgate—two, if you counted the one in the kingdom of Rira, which Iri had sway over. Among Iri’s three monarchs, currently two kings and a queen, the latter had authority over foreign policy, so she was the one they needed to talk to.

“I’m fine with moving up the time,” Dalinar said. “I’ll await you in the writing chamber.”

“Why?” Dalinar said, waving a hand. “It’s not like she can see me. Set up here.”

“Here,” Navani said flatly.

“Here,” Dalinar said, feeling stubborn. “I’ve had enough of cold chambers, silent save for the scratching of reeds.”

Navani raised an eyebrow at him, but ordered her assistants to get out their writing materials. A worried ardent came over, perhaps to try to dissuade her—but after a few firm orders from Navani, he went running to get her a bench and table.

Dalinar smiled and went to select two training swords from a rack near the swordmasters. Common longswords of unsharpened steel. He tossed one to Kadash, who caught it smoothly, but then placed it in front of him with point down, resting his hands on the pommel.

“Brightlord,” Kadash said, “I would prefer to give this task to another, as I don’t particularly feel—”

“Tough,” Dalinar said. “I need some practice, Kadash. As your master, I demand you give it to me.”

Kadash stared at Dalinar for a protracted moment, then let out an annoyed huff and followed Dalinar to the ring. “I won’t be much of a match for you, Brightlord. I have dedicated my years to scripture, not the sword. I was only here to—”

“—check up on me. I know. Well, maybe I’ll be rusty too. I haven’t fought with a common longsword in decades. I always had something better.”

“Yes. I remember when you first got your Blade. The world itself trembled on that day, Dalinar Kholin.”

“Don’t be melodramatic,” Dalinar said. “I was merely one in a long line of idiots given the ability to kill people too easily.”

Rial hesitantly counted the start to the match, and Dalinar rushed in swinging. Kadash rebuffed him competently, then stepped to the side of the ring. “Pardon, Brightlord, but you were different from the others. You were much, much better at the killing part.”

I always have been, Dalinar thought, rounding Kadash. It was odd to remember the ardent as one of his elites. They hadn’t been close then; they’d only become so during Kadash’s years as an ardent.

Navani cleared her throat. “Hate to interrupt this stick-wagging,” she said, “but the queen is ready to speak with you, Dalinar.”

“Great,” he said, not taking his eyes off Kadash. “Read me what she says.”

“While you’re sparring?”

“Sure.”

He could practically feel Navani roll her eyes. He grinned, coming in at Kadash again. She thought he was being silly. Perhaps he was.

He was also failing. One at a time, the world’s monarchs were shutting him out. Only Taravangian of Kharbranth—known to be slow witted— had agreed to listen to him. Dalinar was doing something wrong. In an extended war campaign, he’d have forced himself to look at his problems from a new perspective. Bring in new officers to voice their ideas. Try to approach battles from different terrain.

Dalinar clashed blades with Kadash, smashing metal against metal.

“ ‘Highprince,’ ” Navani read as he fought, “ ‘it is with wondrous awe at the grandeur of the One that I approach you. The time for the world to undergo a glorious new experience has arrived.’ ”

“Glorious, Your Majesty?” Dalinar said, swiping at Kadash’s leg. The man dodged back. “Surely you can’t welcome these events?”

“ ‘All experience is welcome,’” came the reply. “ ‘We are the One experiencing itself—and this new storm is glorious even if it brings pain.’ ”

Dalinar grunted, blocking a backhand from Kadash. Swords rang loudly. “I hadn’t realized,” Navani noted, “that she was so religious.”

“Pagan superstition,” Kadash said, sliding back across the mat from Dalinar. “At least the Azish have the decency to worship the Heralds, although they blasphemously place them above the Almighty. The Iriali are no better than Shin shamans.”

“I remember, Kadash,” Dalinar said, “when you weren’t nearly so judgmental.”

“I’ve been informed that my laxness might have served to encourage you.”

“I always found your perspective to be refreshing.” He stared right at Kadash, but spoke to Navani. “Tell her: Your Majesty, as much as I welcome a challenge, I fear the suffering these new… experiences will bring. We must be unified in the face of the coming dangers.”

“Unity,” Kadash said softly. “If that is your goal, Dalinar, then why do you seek to rip apart your own people?”

Navani started writing. Dalinar drew closer, passing his longsword from one hand to the other. “How do you know, Kadash? How do you know the Iriali are the pagans?”

Kadash frowned. Though he wore the square beard of an ardent, that scar on his head wasn’t the only thing that set him apart from his fellows. They treated swordplay like just another art. Kadash had the haunted eyes of a soldier. When he dueled, he kept watch to the sides, in case someone tried to flank him. An impossibility in a solo duel, but all too likely on a battlefield.

“How can you ask that, Dalinar?”

“Because it should be asked,” Dalinar said. “You claim the Almighty is God. Why?”

“Because he simply is.”

“That isn’t good enough for me,” Dalinar said, realizing for the first time it was true. “Not anymore.”

The ardent growled, then leaped in, attacking with real determination this time. Dalinar danced backward, fending him off, as Navani read— loudly.

“ ‘Highprince, I will be frank. The Iriali Triumvirate is in agreement. Alethkar has not been relevant in the world since the Sunmaker’s fall. The power of the ones who control the new storm, however, is undeniable. They offer gracious terms.’ ”

Dalinar stopped in place, dumbfounded. “You’d side with the Voidbringers?” he asked toward Navani, but then was forced to defend himself from Kadash, who hadn’t let up.

“What?” Kadash said, clanging his blade against Dalinar’s. “Surprised someone is willing to side with evil, Dalinar? That someone would pick darkness, superstition, and heresy instead of the Almighty’s light?”

“I am not a heretic.” Dalinar slapped Kadash’s blade away—but not before the ardent scored a touch on Dalinar’s arm. The hit was hard, and though the swords were blunted, that would bruise for certain.

“You just told me you doubted the Almighty,” Kadash said. “What is left, after that?”

“I don’t know,” Dalinar said. He stepped closer. “I don’t know, and that terrifies me, Kadash. But Honor spoke to me, confessed that he was beaten.”

“The princes of the Voidbringers,” Kadash said, “were said to be able to blind the eyes of men. To send them lies, Dalinar.”

He rushed in, swinging, but Dalinar danced back, retreating around the rim of the dueling ring.

“ ‘My people,’” Navani said, reading the reply from the queen of Iri, “ ‘do not want war. Perhaps the way to prevent another Desolation is to let the Voidbringers take what they wish. From our histories, sparse though they are, it seems that this was the one option men never explored. An experience from the One we rejected.’ ”

Navani looked up, obviously as surprised to read the words as Dalinar was to hear them. The pen kept writing. “ ‘Beyond that,’ ” she added, “ ‘we have reasons to distrust the word of a thief, Highprince Kholin.’ ”

Dalinar groaned. So that was what this was all about—Adolin’s Shardplate. Dalinar glanced at Navani. “Find out more, try to console them?”

She nodded, and started writing. Dalinar gritted his teeth and charged Kadash again. The ardent caught his sword, then grabbed his takama with his free hand, pulling him close, face to face.

“The Almighty is not dead,” Kadash hissed.

“Once, you’d have counseled me. Now you glare at me. What happened to the ardent I knew? A man who had lived a real life, not just watched the world from high towers and monasteries?”

“He’s frightened,” Kadash said softly. “That he’s somehow failed in his most solemn duty to a man he deeply admires.”

They met eyes, their swords still locked, but neither one actually trying to push the other. For a moment, Dalinar saw in Kadash the man he’d always been. The gentle, understanding model of everything good about the Vorin church.

“Give me something to take back to the curates of the church,” Kadash pled. “Recant your insistence that the Almighty is dead. If you do that, I can make them accept the marriage. Kings have done worse and retained Vorin support.”

Dalinar set his jaw, then shook his head.

“Dalinar…”

“Falsehoods serve nobody, Kadash,” Dalinar said, pulling back. “If the Almighty is dead, then pretending otherwise is pure stupidity. We need real hope, not faith in lies.”

Around the room, more than a few men had stopped their bouts to watch or listen. The swordmasters had stepped up behind Navani, who was still exchanging some politic words with the Iriali queen.

“Don’t throw out everything we’ve believed because of a few dreams, Dalinar,” Kadash said. “What of our society, what of tradition?”

“Tradition?” Dalinar said. “Kadash, did I ever tell you about my first sword trainer?”

“No,” Kadash said, frowning, glancing at the other ardents. “Was it Rembrinor?”

Dalinar shook his head. “Back when I was young, our branch of the Kholin family didn’t have grand monasteries and beautiful practice grounds. My father found a teacher for me from two towns over. His name was Harth. Young fellow, not a true swordmaster—but good enough.

“He was very focused on proper procedure, and wouldn’t let me train until I’d learned how to put on a takama the right way.” Dalinar gestured at the takama shirt he was wearing. “He wouldn’t have stood for me fighting like this. You put on the skirt, then the overshirt, then you wrap your cloth belt around yourself three times and tie it.

“I always found that annoying. The belt was too tight, wrapped three times—you had to pull it hard to get enough slack to tie the knot. The first time I went to duels at a neighboring town, I felt like an idiot. Everyone else had long drooping belt ends at the front of their takamas.

“I asked Harth why we did it differently. He said it was the right way, the true way. So, when my travels took me to Harth’s hometown, I searched out his master, a man who had trained with the ardents in Kholinar. He insisted that this was the right way to tie a takama, as he’d learned from his master.”

By now, they’d drawn an even larger crowd. Kadash frowned. “And the point?”

“I found my master’s master’s master in Kholinar after we captured it,” Dalinar said. “The ancient, wizened ardent was eating curry and flatbread, completely uncaring of who ruled the city. I asked him. Why tie your belt three times, when everyone else thinks you should do it twice?

“The old man laughed and stood up. I was shocked to see that he was terribly short. ‘If I only tie it twice,’ he exclaimed, ‘the ends hang down so low, I trip!’ ”

The chamber fell silent. Nearby, one soldier chuckled, but quickly cut himself off—none of the ardents seemed amused.

“I love tradition,” Dalinar said to Kadash. “I’ve fought for tradition. I make my men follow the codes. I uphold Vorin virtues. But merely being tradition does not make something worthy, Kadash. We can’t just assume that because something is old it is right.”

He turned to Navani.

“She’s not listening,” Navani said. “She insists you are a thief, not to be trusted.”

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “I am led to believe that you would let nations fall, and men be slaughtered, because of a petty grievance from the past. If my relations with the kingdom of Rira are prompting you to consider supporting the enemies of all humankind, then perhaps we could discuss a personal reconciliation first.”

Navani nodded at that, though she glanced at the people watching and cocked an eyebrow. She thought all this should have been done in private. Well, perhaps she was right. At the same time, Dalinar felt he’d needed this. He couldn’t explain why.

He raised his sword to Kadash in a sign of respect. “Are we done here?”

In response, Kadash came running at him, sword raised. Dalinar sighed, then let himself get touched on the left, but ended the exchange with his weapon leveled at Kadash’s neck.

“That’s not a valid dueling strike,” the ardent said.

“I’m not much of a duelist these days.”

The ardent grunted, then shoved away Dalinar’s weapon and lunged at him. Dalinar, however, caught Kadash’s arm, then spun the man with his own momentum. He slammed Kadash down to the ground and held him there.

“The world is ending, Kadash,” Dalinar said. “I can’t simply rely on tradition. I need to know why. Convince me. Offer me proof of what you say.” “You shouldn’t need proof in the Almighty. You sound like your niece!”

“I’ll take that as a compliment.”

“What… what of the Heralds?” Kadash said. “Do you deny them, Dalinar? They were servants of the Almighty, and their existence proved his. They had power.”

“Power?” Dalinar said. “Like this?”

He sucked in Stormlight. Murmuring rose from those watching as Dalinar began to glow, then did… something else. Commanded the Light. When he rose, he left Kadash stuck to the ground in a pool of Radiance that held him fast, binding him to the stone. The ardent wriggled, helpless.

“The Knights Radiant have returned,” Dalinar said. “And yes, I accept the authority of the Heralds. I accept that there was a being, once, named Honor—the Almighty. He helped us, and I would welcome his help again. If you can prove to me that Vorinism as it currently stands is what the Heralds taught, we will speak again.”

He tossed his sword aside and stepped up to Navani.

“Nice show,” she said softly. “That was for the room, not just Kadash, I assume?”

“The soldiers need to know where I stand in relation to the church.

What does our queen say?”

“Nothing good,” she muttered. “She says you can contact her with arrangements for the return of the stolen goods, and she’ll consider.”

“Storming woman,” Dalinar said. “She’s after Adolin’s Shardplate. How valid is her claim?”

“Not very,” Navani said. “You got that through marriage, and to a lighteyes from Rira, not Iri. Yes, the Iriali claim their sister nation as a vassal, but even if the claim weren’t disputed, the queen doesn’t have any actual relation to Evi or her brother.”

Dalinar grunted. “Rira was never strong enough to try to claim the Plate back. But if it will bring Iri to our side, then I’d consider it. Maybe I can agree to…” He trailed off. “Wait. What did you say?”

“Hum?” Navani said. “About… oh, right. You can’t hear her name.” “Say it again,” Dalinar whispered.

“What?” Navani said. “Evi?”

Memories blossomed in Dalinar’s head. He staggered, then slumped against the writing table, feeling as if he’d been struck by a hammer to the head. Navani called for physicians, implying his dueling had overtaxed him.

That wasn’t it. Instead, it was the burning in his mind, the sudden shock of a word spoken.

Evi. He could hear his wife’s name.

And he suddenly remembered her face.

Chapter 17

Trapped in Shadows

It is not a lesson I claim to be able to teach. Experience herself is the great teacher, and you must seek her directly.

—From Oathbringer, preface

I still think we should kill him,” Khen—the parshwoman who had been playing cards—said to the others.

Kaladin sat tied and bound to a tree. He’d spent the night there. They’d let him up several times to use the latrine today, but otherwise kept him bound. Though their knots were good, they always posted guards, even though he’d turned himself in to them in the first place.

His muscles were stiff, and the posture was uncomfortable, but he had endured worse as a slave. Almost the entire afternoon had passed so far— and they were still arguing about him.

He didn’t see that yellow-white spren again, the one that had been a ribbon of light. He almost thought he’d imagined it. At least the rain had finally stopped. Hopefully that meant the highstorms—and Stormlight— were close to returning.

“Kill him?” another of the parshmen said. “Why? What danger is he to us?”

“He’ll tell others where we are.”

“He found us easily enough on his own. I doubt others will have trouble, Khen.”

The parshmen didn’t seem to have a specific leader. Kaladin could hear them talking from where they stood, huddled together beneath a tarp. The air smelled wet, and the clump of trees shivered when a gust of wind blew through. A shower of water drops came down on top of him, somehow more cold than the Weeping itself.

Soon, blessedly, this would all dry up and he could finally see the sun again.

“So we let him go?” Khen asked. She had a gruff voice, angry.

“I don’t know. Would you actually do it, Khen? Bash his head in yourself ?”

The tent fell silent.

“If it means they can’t take us again?” she said. “Yes, I’d kill him. I won’t go back, Ton.”

They had simple, darkeyed Alethi names—matched by their uncomfortably familiar accents. Kaladin didn’t worry for his safety; though they’d taken his knife, spanreed, and spheres, he could summon Syl at a moment’s notice. She flitted nearby on gusts of wind, dodging between the branches of trees.

The parshmen eventually left their conference, and Kaladin dozed. He was later roused by the noise of them gathering up their meager belongings: an axe or two, some waterskins, the nearly ruined bags of grain. As the sun set, long shadows stretched across Kaladin, plunging the camp into darkness again. It seemed that the group moved at night.

The tall male who had been playing cards the night before approached Kaladin, who recognized the pattern of his skin. He untied the ropes binding Kaladin to the tree, the ones around his ankles—but left the bonds on Kaladin’s hands.

“You could capture that card,” Kaladin noted.

The parshman stiffened.

“The card game,” Kaladin said. “The squire can capture if supported by an allied card. So you were right.”

The parshman grunted, yanking on the rope to tow Kaladin to his feet. He stretched, working stiff muscles and painful cramps, as the other parshmen broke down the last of the improvised tarp tents: the one that had been fully enclosed. Earlier in the day, though, Kaladin had gotten a look at what was inside.

Children.

There were a dozen of them, dressed in smocks, of various ages from toddler to young teenager. The females wore their hair loose, and the males wore theirs tied or braided. They hadn’t been allowed to leave the tent except at a few carefully supervised moments, but he had heard them laughing. He’d first worried they were captured human children.

As the camp broke, they scattered about, excited to finally be released. One younger girl scampered across the wet stones and seized the empty hand of the man leading Kaladin. Each of the children bore the distinctive look of their elders—the not-quite-Parshendi appearance with the armored portions on the sides of their heads and forearms. For the children, the color of the carapace was a light orange-pink.

Kaladin couldn’t define why this sight seemed so strange to him. Parshmen did breed, though people often spoke of them being bred, like animals. And, well, that wasn’t far from the truth, was it? Everyone knew it.

What would Shen—Rlain—think if Kaladin had said those words out loud?

The procession moved out of the trees, Kaladin led by his ropes. They kept talk to a minimum, and as they crossed through a field in the darkness, Kaladin had a distinct impression of familiarity. Had he been here before, done this before?

“What about the king?” his captor said, speaking in a soft voice, but turning his head to direct the question at Kaladin.

Elhokar? What… Oh, right. The cards.

“The king is one of the most powerful cards you can place,” Kaladin said, struggling to remember all the rules. “He can capture any other card except another king, and can’t be captured himself unless touched by three enemy cards of knight or better. Um… and he is immune to the Soulcaster.” I think.

“When I watched men play, they used this card rarely. If it is so powerful, why delay?”

“If your king gets captured, you lose,” Kaladin said. “So you only play him if you’re desperate or if you are certain you can defend him. Half the times I’ve played, I left him in my barrack all game.”

The parshman grunted, then looked to the girl at his side, who tugged on his arm and pointed. He gave her a whispered response, and she ran on tiptoes toward a patch of flowering rockbuds, visible by the light of the first moon.

The vines pulled back, blossoms closing. The girl, however, knew to squat at the side and wait, hands poised, until the flowers reopened—then she snatched one in each hand, her giggles echoing across the plain. Joyspren followed her like blue leaves as she returned, giving Kaladin a wide berth.

Khen, walking with a cudgel in her hands, urged Kaladin’s captor to keep moving. She watched the area with the nervousness of a scout on a dangerous mission.

That’s it, Kaladin thought, remembering why this felt familiar. Sneaking away from Tasinar.

It had happened after he’d been condemned by Amaram, but before he’d been sent to the Shattered Plains. He avoided thinking of those months. His repeated failures, the systematic butchering of his last hints of idealism… well, he’d learned that dwelling on such things took him to dark places. He’d failed so many people during those months. Nalma had been one of those. He could remember the touch of her hand in his: a rough, callused hand.

That had been his most successful escape attempt. It had lasted five days.

“You’re not monsters,” Kaladin whispered. “You’re not soldiers. You’re not even the seeds of the void. You’re just… runaway slaves.”

His captor spun, yanking on Kaladin’s rope. The parshman seized Kaladin by the front of his uniform, and his daughter hid behind his leg, dropping one of her flowers and whimpering.

“Do you want me to kill you?” the parshman asked, pulling Kaladin’s face close to his own. “You insist on reminding me how your kind see us?”

Kaladin grunted. “Look at my forehead, parshman.”

“And?”

“Slave brands.”

“What?”

Storms… parshmen weren’t branded, and they didn’t mix with other slaves. Parshmen were actually too valuable for that. “When they make a human into a slave,” Kaladin said, “they brand him. I’ve been here. Right where you are.”

“And you think that makes you understand?”

“Of course it does. I’m one—”

“I have spent my entire life living in a fog,” the parshman yelled at him. “Every day knowing I should say something, do something to stop this! Every night clutching my daughter, wondering why the world seems to move around us in the light—while we are trapped in shadows. They sold her mother. Sold her. Because she had birthed a healthy child, which made her good breeding stock.

“Do you understand that, human? Do you understand watching your family be torn apart, and knowing you should object—knowing deep in your soul that something is profoundly wrong? Can you know that feeling of being unable to say a single storming word to stop it?”

The parshman pulled him even closer. “They may have taken your freedom, but they took our minds.”

He dropped Kaladin and whirled, gathering up his daughter and holding her close as he jogged to catch up to the others, who had turned back at the outburst. Kaladin followed, yanked by his rope, stepping on the little girl’s flower in his forced haste. Syl zipped past, and when Kaladin tried to catch her attention, she just laughed and flew higher on a burst of wind.

His captor suffered several quiet chastisements when they caught up; this column couldn’t afford to draw attention. Kaladin walked with them, and remembered. He did understand a little.

You were never free while you ran; you felt as if the open sky and the endless fields were a torment. You could feel the pursuit following, and each morning you awoke expecting to find yourself surrounded.

Until one day you were right.

But parshmen? He’d accepted Shen into Bridge Four, yes. But accepting that a sole parshman could be a bridgeman was starkly different from accepting the entire people as… well, human.

As the column stopped to distribute waterskins to the children, Kaladin felt at his forehead, tracing the scarred shape of the glyphs there.

They took our minds.…

They’d tried to take his mind too. They’d beaten him to the stones, stolen everything he loved, and murdered his brother. Left him unable to think straight. Life had become a blur until one day he’d found himself standing over a ledge, watching raindrops die and struggling to summon the motivation to end his life.

Syl soared past in the shape of a shimmering ribbon.

“Syl,” Kaladin hissed. “I need to talk to you. This isn’t the time for—”

“Hush,” she said, then giggled and zipped around him before flitting over and doing the same to his captor.

Kaladin frowned. She was acting so carefree. Too carefree? Like she’d been back before they forged their bond?

No. It couldn’t be.

“Syl?” he begged as she returned. “Is something wrong with the bond? Please, I didn’t—”

“It’s not that,” she said, speaking in a furious whisper. “I think parshmen might be able to see me. Some, at least. And that other spren is still here too. A higher spren, like me.”

“Where?” Kaladin asked, twisting.

“He’s invisible to you,” Syl said, becoming a group of leaves and blowing around him. “I think I’ve fooled him into thinking I’m just a windspren.”

She zipped away, leaving a dozen unanswered questions on Kaladin’s lips. Storms… is that spren how they know where to go?

The column started again, and Kaladin walked for a good hour in silence before Syl next decided to come back to him. She landed on his shoulder, becoming the image of a young woman in her whimsical skirt. “He’s gone ahead for a little bit,” she said. “And the parshmen aren’t looking.”

“The spren is guiding them,” Kaladin said under his breath. “Syl, this spren must be…”

“From him,” she whispered, wrapping her arms around herself and growing small—actively shrinking to about two-thirds her normal size. “Voidspren.”

“There’s more,” Kaladin said. “These parshmen… how do they know how to talk, how to act? Yes, they’ve spent their lives around society—but to be this, well, normal after such a long time half asleep?”

“The Everstorm,” Syl said. “Power has filled the holes in their souls, bridging the gaps. They didn’t just wake, Kaladin. They’ve been healed, Connection refounded, Identity restored. There’s more to this than we ever realized. Somehow when you conquered them, you stole their ability to change forms. You literally ripped off a piece of their souls and locked it away.” She turned sharply. “He’s coming back. I will stay nearby, in case you need a Blade.”

She left, zipping straight into the air as a ribbon of light. Kaladin continued to shuffle behind the column, chewing on her words, before speeding up and stepping beside his captor.

“You’re being smart, in some ways,” Kaladin said. “It’s good to travel at night. But you’re following the riverbed over there. I know it makes for more trees, and more secure camping, but this is literally the first place someone would look for you.”

Several of the other parshmen gave him glances from nearby. His captor didn’t say anything.

“The big group is an issue too,” Kaladin added. “You should break into smaller groups and meet up each morning, so if you get spotted you’ll seem less threatening. You can say you were sent somewhere by a lighteyes, and travelers might let you go. If they run across all seventy of you together, there’s no chance of that. This is all assuming, of course, you don’t want to fight—which you don’t. If you fight, they’ll call out the highlords against you. For now they’ve got bigger problems.”

His captor grunted.

“I can help you,” Kaladin said. “I might not understand what you’ve been through, but I do know what it feels like to run.”

“You think I’d trust you?” the parshman finally said. “You will want us to be caught.”

“I’m not sure I do,” Kaladin said, truthful.

His captor said nothing more and Kaladin sighed, dropping back into position behind. Why had the Everstorm not granted these parshmen powers like those on the Shattered Plains? What of the stories of scripture and lore? The Desolations?

They eventually stopped for another break, and Kaladin found himself a smooth rock to sit against, nestled into the stone. His captor tied the rope to a nearby lonely tree, then went to confer with the others. Kaladin leaned back, lost in thought until he heard a sound. He was surprised to find his captor’s daughter approaching. She carried a waterskin in two hands, and stopped right beyond his reach.

She didn’t have shoes, and the walk so far had not been kind to her feet, which—though tough with calluses—were still scored by scratches and scrapes. She timidly set the waterskin down, then backed away. She didn’t flee, as Kaladin might have expected, when he reached for the water.

“Thank you,” he said, then took a mouthful. It was pure and clear— apparently the parshmen knew how to settle and scoop their water. He ignored the rumbling of his stomach.

“Will they really chase us?” the girl asked.

By Mishim’s pale green light, he decided this girl was not as timid as he had assumed. She was nervous, but she met his eyes with hers.

“Why can’t they just let us go?” she asked. “Could you go back and tell them? We don’t want trouble. We just want to go away.”

“They’ll come,” Kaladin said. “I’m sorry. They have a lot of work to do in rebuilding, and they’ll want the extra hands. You are a… resource they can’t simply ignore.”

The humans he’d visited hadn’t known to expect some terrible Voidbringer force; many thought their parshmen had merely run off in the chaos.

“But why?” she said, sniffling. “What did we do to them?”

“You tried to destroy them.”

“No. We’re nice. We’ve always been nice. I never hit anyone, even when I was mad.”

“I didn’t mean you specifically,” Kaladin said. “Your ancestors—the people like you from long ago. There was a war, and…”

Storms. How did you explain slavery to a seven-year-old? He tossed the waterskin to her, and she scampered back to her father—who had only just noticed her absence. He stood, a stark silhouette in the night, studying Kaladin.

“They’re talking about making camp,” Syl whispered from nearby. She had crawled into a crack in the rock. “The Voidspren wants them to march on through the day, but I don’t think they’re going to. They’re worried about their grain spoiling.”

“Is that spren watching me right now?” Kaladin asked. “No.”

“Then let’s cut this rope.”

He turned and hid what he was doing, then quickly summoned Syl as a knife to cut himself free. That would change his eye color, but in the darkness, he hoped the parshmen wouldn’t notice.

Syl puffed back into a spren. “Sword now?” she said. “The spheres they took from you have all run out, but they’ll scatter at seeing a Blade.”

“No.” Kaladin instead picked up a large stone. The parshmen hushed, noticing his escape. Kaladin carried his rock a few steps, then dropped it, crushing a rockbud. He was surrounded a few moments later by angry parshmen carrying cudgels.

Kaladin ignored them, picking through the wreckage of the rockbud. He held up a large section of shell.

“The inside of this,” he said, turning it over for them, “will still be dry, despite the rainfall. The rockbud needs a barrier between itself and the water outside for some reason, though it always seems eager to drink after a storm. Who has my knife?”

Nobody moved to return it.

“If you scrape off this inner layer,” Kaladin said, tapping at the rockbud shell, “you can get to the dry portion. Now that the rain has stopped, I should be able to get us a fire going, assuming nobody has lost my tinder bag. We need to boil that grain, then dry it into cakes. They won’t be tasty, but they’ll keep. If you don’t do something soon, your supplies will rot.”

He stood up and pointed. “Since we’re already here, we should be near enough the river that we can gather more water. It won’t flow much longer with the end of the rains.

“Rockbud shells don’t burn particularly well, so we’ll want to harvest some real wood and dry it at the fire during the day. We can keep that one small, then do the cooking tomorrow night. In the dark, the smoke is less likely to reveal us, and we can shield the light in the trees. I just have to figure out how we’re going to cook without any pots to boil the water.”

The parshmen stared at him. Then Khen finally pushed him away from the rockbud and took up the shard he’d been holding. Kaladin spotted his original captor standing near the rock where Kaladin had been sitting. The parshman held the rope Kaladin had cut, rubbing its sliced-through end with his thumb.

After a short conference, the parshmen dragged him to the trees he’d indicated, returned his knife—standing by with every cudgel they had— and demanded that he prove he could build a fire with wet wood.

He did just that.

Chapter18

Double Vision

You cannot have a spice described to you, but must taste it for yourself.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Shallan became Veil.

Stormlight made her face less youthful, more angular. Nose pointed, with a small scar on the chin. Her hair rippled from red to Alethi black. Making an illusion like this took a larger gem of Stormlight, but once it was going, she could maintain it for hours on just a smidgen.

Veil tossed aside the havah, instead pulling on trousers and a tight shirt, then boots and a long white coat. She finished with only a simple glove on the left hand. Veil, of course, wasn’t in the least embarrassed at that.

There was a simple relief for Shallan’s pain. There was an easy way to hide. Veil hadn’t suffered as Shallan had—and she was tough enough to handle that sort of thing anyway. Becoming her was like setting down a terrible burden.

Veil threw a scarf around her neck, then slung a rugged satchel— acquired for Veil specifically—over her shoulder. Hopefully the conspicuous knife handle sticking out from the top would look natural, even intimidating.

The part at the back of her mind that was still Shallan worried about this. Would she look fake? She’d almost certainly missed some subtle clues encoded in her behavior, dress, or speech. These would indicate to the right people that Veil didn’t have the hard-bitten experience she feigned.

Well, she would have to do her best and hope to recover from her inevitable mistakes. She tied another knife onto her belt, long, but not quite a sword, since Veil wasn’t lighteyed. Fortunately. No lighteyed woman would be able to prance around so obviously armed. Some mores grew lax the farther you descended the social ladder.

“Well?” Veil asked, turning to the wall, where Pattern hung.

“Mmm…” he said. “Good lie.”

“Thank you.”

“Not like the other.”

“Radiant?”

“You slip in and out of her,” Pattern said, “like the sun behind clouds.”

“I just need more practice,” Veil said. Yes, that voice sounded excellent.

Shallan was getting far better with sounds.

She picked Pattern up—which involved pressing her hand against the wall, letting him pass over to her skin and then her coat. With him humming happily, she crossed her room and stepped out onto the balcony. The first moon had risen, violet and proud Salas. She was the least bright of the moons, which meant it was mostly dark out.

Most rooms on the outside had these small balconies, but hers on the second level was particularly advantageous. It had steps down to the field below. Covered in furrows for water and ridges for planting rockbuds, the field also had boxes at the edges for growing tubers or ornamental plants. Each tier of the city had a similar one, with eighteen levels inside separating them.

She stepped down to the field in the darkness. How had anything ever grown up here? Her breath puffed out in front of her, and coldspren grew around her feet.

The field had a small access doorway back into Urithiru. Perhaps the subterfuge of not exiting through her room wasn’t necessary, but Veil preferred to be careful. She wouldn’t want guards or servants remarking on how Brightness Shallan went about during odd hours of the night.

Besides, who knew where Mraize and his Ghostbloods had operatives? They hadn’t contacted her since that first day in Urithiru, but she knew they’d be watching. She still didn’t know what to do about them. They had admitted to assassinating Jasnah, which should be grounds enough to hate them. They also seemed to know things, important things, about the world.

Veil strolled through the corridor, carrying a small hand lamp for light, as a sphere would make her stand out. She passed evening crowds that kept the corridors of Sebarial’s quarter as busy as his warcamp had been. Things never seemed to slow down here as much as they did in Dalinar’s quarter.

The strangely mesmerizing strata of the corridors guided her out of Sebarial’s quarter. The number of people in the hallways slackened. Just Veil and those lonely, endless tunnels. She felt as if she could sense the weight of the other levels of the tower, empty and unexplored, bearing down on her. A mountain of unknown stone.

She hurried on her way, Pattern humming to himself from her coat.

“I like him,” Pattern said.

“Who?” Veil said.

“The swordsman,” Pattern said. “Mmm. The one you can’t mate with yet.”

“Can we please stop talking about him that way?”

“Very well,” Pattern said. “But I like him.”

“You hate his sword.”

“I have come to understand,” Pattern said, growing excited. “Humans… humans don’t care about the dead. You build chairs and doors out of corpses! You eat corpses! You make clothing from the skins of corpses. Corpses are things to you.”

“Well, I guess that’s true.” He seemed unnaturally excited by the revelation.

“It is grotesque,” he continued, “but you all must kill and destroy to live. It is the way of the Physical Realm. So I should not hate Adolin Kholin for wielding a corpse!”

“You just like him,” Veil said, “because he tells Radiant to respect the sword.”

“Mmm. Yes, very, very nice man. Wonderfully smart too.”

“Why don’t you marry him, then?”

Pattern buzzed. “Is that—”

“No that’s not an option.”

“Oh.” He settled down into a contented buzz on her coat, where he appeared as a strange kind of embroidery.

After a short time walking, Shallan found she needed to say something more. “Pattern. Do you remember what you said to me the other night, the first time… we became Radiant?”

“About dying?” Pattern asked. “It may be the only way, Shallan. Mmm… You must speak truths to progress, but you will hate me for making it happen. So I can die, and once done you can—”

“No. No, please don’t leave me.”

“But you hate me.”

“I hate myself too,” she whispered. “Just… please. Don’t go. Don’t die.” Pattern seemed pleased by this, as his humming increased—though his sounds of pleasure and his sounds of agitation could be similar. For the moment, Veil let herself be distracted by the night’s quest. Adolin continued his efforts to find the murderer, but hadn’t gotten far. Aladar was Highprince of Information, and his policing force and scribes were a resource—but Adolin wanted badly to do as his father asked.

Veil thought that perhaps both were looking in the wrong places. She finally saw lights ahead and quickened her pace, eventually stepping out onto a walkway around a large cavernous room that stretched up several stories. She had reached the Breakaway: a vast collection of tents lit by many flickering candles, torches, or lanterns.

The market had sprung up shockingly fast, in defiance of Navani’s carefully outlined plans. Her idea had been for a grand thoroughfare with shops along the sides. No alleyways, no shanties or tents. Easily patrolled and carefully regulated.

The merchants had rebelled, complaining about lack of storage space, or the need to be closer to a well for fresh water. In reality, they wanted a larger market that was much harder to regulate. Sebarial, as Highprince of Commerce, had agreed. And despite having made a mess of his ledgers, he was sharp when it came to trade.

The chaos and variety of it excited Veil. Hundreds of people, despite the hour, attracting spren of a dozen varieties. Dozens upon dozens of tents of varied colors and designs. In fact, some weren’t tents at all, but were better described as stands—roped-off sections of ground guarded by a few burly men with cudgels. Others were actual buildings. Small stone sheds that had been built inside this cavern, here since the days of the Radiants.

Merchants from all ten original warcamps mixed at the Breakaway. She passed three different cobblers in a row; Veil had never understood why merchants selling the same things congregated. Wouldn’t it be better to set up where you wouldn’t have competition literally next door?

She packed away her hand lamp, as there was plenty of light here from the merchant tents and shops, and sauntered along. Veil felt more comfortable than she had in those empty, twisted corridors; here, life had gained a foothold. The market grew like the snarl of wildlife and plants on the leeward side of a ridge.

She made her way to the cavern’s central well: a large, round enigma that rippled with crem-free water. She’d never seen an actual well before— everyone normally used cisterns that refilled with the storms. The many wells in Urithiru, however, never ran out. The water level didn’t even drop, despite people constantly drawing from them.

Scribes talked about the possibility of a hidden aquifer in the mountains, but where would the water come from? Snows at the tops of the peaks nearby didn’t seem to melt, and rain fell very rarely.

Veil sat on the well’s side, one leg up, watching the people who came and went. She listened to the women chatter about the Voidbringers, about family back in Alethkar, and about the strange new storm. She listened to the men worry about being pressed into the military, or about their darkeyed nahn being lowered, now that there weren’t parshmen to do common work. Some lighteyed workers complained about supplies trapped back in Narak, waiting for Stormlight before they could be transferred here.

Veil eventually ambled off toward a particular row of taverns. I can’t interrogate too hard to get my answers, she thought. If I ask the wrong kind of questions, everyone will figure me for some kind of spy for Aladar’s policing force.

Veil. Veil didn’t hurt. She was comfortable, confident. She’d meet people’s eyes. She’d lift her chin in challenge to anyone who seemed to be sizing her up. Power was an illusion of perception.

Veil had her own kind of power, that of a lifetime spent on the streets knowing she could take care of herself. She had the stubbornness of a chull, and while she was cocky, that confidence was a power of its own. She got what she wanted and wasn’t embarrassed by success.

The first bar she chose was inside a large battle tent. It smelled of spilled lavis beer and sweaty bodies. Men and women laughed, using overturned crates as tables and chairs. Most wore simple darkeyed clothing: laced shirts—no money or time for buttons—and trousers or skirts. A few men dressed after an older fashion, with a wrap and a loose filmy vest that left the chest exposed.

This was a low-end tavern, and likely wouldn’t work for her needs. She’d need a place that was lower, yet somehow richer. More disreputable, but with access to the powerful members of the warcamp undergrounds.

Still, this seemed a good place to practice. The bar was made of stacked boxes and had some actual chairs beside it. Veil leaned against the “bar” in what she hoped was a smooth way, and nearly knocked the boxes over. She stumbled, catching them, then smiled sheepishly at the bartender—an old darkeyed woman with grey hair.

“What do you want?” the woman asked.

“Wine,” Veil said. “Sapphire.” The second most intoxicating. Let them see that Veil could handle the hard stuff.

“We got Vari, kimik, and a nice barrel of Veden. That one will cost you though.”

“Uh…” Adolin would have known the differences. “Give me the Veden.” Seemed appropriate.

The woman made her pay first, with dun spheres, but the cost didn’t seem outrageous. Sebarial wanted the liquor flowing—his suggested way to make sure tensions didn’t get too high in the tower—and had subsidized the prices with low taxes, for now.

While the woman worked behind her improvised bar, Veil suffered beneath the gaze of one of the bouncers. Those didn’t stay near the entrance, but instead waited here, beside the liquor and the money. Despite what Aladar’s policing force would like, this place was not completely safe. If unexplained murders had been glossed over or forgotten, they would have happened in the Breakaway, where the clutter, worry, and press of tens of thousands of camp followers balanced on the edge of lawlessness.

The barkeep plunked a cup in front of Veil—a tiny cup, with a clear liquid in it.

Veil scowled, holding it up. “You got mine wrong, barkeep; I ordered sapphire. What is this, water?”

The bouncer nearest Veil snickered, and the barkeep stopped in place, then looked her over. Apparently Shallan had already made one of those mistakes she’d been worried about.

“Kid,” the barkeep said, somehow leaning on the boxes near her and not knocking any over. “That’s the same stuff, just without the fancy infusions the lighteyes put in theirs.”

Infusions?

“You some kind of house servant?” the woman asked softly. “Out for your first night on your own?”

“Of course not,” Veil said. “I’ve done this a hundred times.”

“Sure, sure,” the woman replied, tucking a stray strand of hair behind her ear. It popped right back up. “You certain you want that? I might have some wines back here done with lighteyed colors, for you. In fact, I know I’ve got a nice orange.” She reached to reclaim the cup.

Veil seized it and knocked the entire thing back in a single gulp. That proved to be one of the worst mistakes of her life. The liquid burned, like it was on fire! She felt her eyes go wide, and she started coughing and almost threw up right there on the bar.

That was wine? Tasted more like lye. What was wrong with these people? There was no sweetness to it at all, not even a hint of flavor. Just that burning sensation, like someone was scraping her throat with a scouring brush! Her face immediately grew warm. It hit her so fast!

The bouncer was holding his face, trying—and failing—not to laugh out loud. The barkeep patted Shallan on the back as she kept coughing. “Here,” the woman said, “let me get you something to chase that—”

“No,” Shallan croaked. “I’m just happy to be able to drink this… again after so long. Another. Please.”

The barkeep seemed skeptical, though the bouncer was all for it—he’d settled down on the stool to watch Shallan, grinning. Shallan placed a sphere on the bar, defiant, and the barkeep reluctantly filled her cup again. By now, three or four other people from nearby seats had turned to watch.

Lovely. Shallan braced herself, then drank the wine in a long, extended gulp.

It wasn’t any better the second time. She held for a moment, eyes watering, then let out an explosion of coughing. She ended up hunched over, shaking, eyes squeezed closed. She was pretty sure she let out a long squeak as well.

Several people in the tent clapped. Shallan looked back at the amused barkeep, her eyes watering. “That was awful,” she said, then coughed. “You really drink this dreadful liquid?”

“Oh, hon,” the woman said. “That’s not nearly as bad as they get.”

Shallan groaned. “Well, get me another.”

“You sure—”

“Yes,” Shallan said with a sigh. She probably wasn’t going to be establishing a reputation for herself tonight—at least not the type she wanted. But she could try to accustom herself to drinking this cleaning fluid.

Storms. She was already feeling lighter. Her stomach did not like what she was doing to it, and she shoved down a bout of nausea.

Still chuckling, the bouncer moved a seat closer to her. He was a younger man, with hair cut so short it stood up on end. He was as Alethi as they came, with a deep tan skin and a dusting of black scrub on his chin.

“You should try sipping it,” he said to her. “Goes down easier in sips.”

“Great. That way I can savor the terrible flavor. So bitter! Wine is supposed to be sweet.”

“Depends on how you make it,” he said as the barkeep gave Shallan another cup. “Sapphire can sometimes be distilled tallew, no natural fruit in it—just some coloring for accent. But they don’t serve the really hard stuff at lighteyed parties, except to people who know how to ask for it.”

“You know your alcohol,” Veil said. The room shook for a moment before settling. Then she tried another drink—a sip this time.

“It comes with the job,” he said with a broad smile. “I work a lot of fancy events for the lighteyes, so I know my way around a place with tablecloths instead of boxes.”

Veil grunted. “They need bouncers at fancy lighteyed events?”

“Sure,” he said, cracking his knuckles. “You just have to know how to ‘escort’ someone out of the feast hall, instead of throwing them out. It’s actually easier.” He cocked his head. “But strangely, more dangerous at the same time.” He laughed.

Kelek, Veil realized as he scooted closer. He’s flirting with me.

She probably shouldn’t have found it so surprising. She’d come in alone, and while Shallan would never have described Veil as “cute,” she wasn’t ugly. She was kind of normal, if rugged, but she dressed well and obviously had money. Her face and hands were clean, her clothing—while not rich silks—a generous step up from worker garb.

Initially she was offended by his attention. Here she’d gone to all this trouble to make herself capable and hard as rocks, and the first thing she did was attract some guy? One who cracked his knuckles and tried to tell her how to drink her alcohol?

Just to spite him, she downed the rest of her cup in a single shot.

She immediately felt guilty for her annoyance at the man. Shouldn’t she be flattered? Granted, Adolin could have destroyed this man in any conceivable way. Adolin even cracked his knuckles louder.

“So…” the bouncer said. “Which warcamp you from?”

“Sebarial,” Veil said.

The bouncer nodded, as if he’d expected that. Sebarial’s camp had been the most eclectic. They chatted a little longer, mostly with Shallan making the odd comment while the bouncer—his name was Jor—went off on various stories with many tangents. Always smiling, often boasting.

He wasn’t too bad, though he didn’t seem to care what she actually said, so long as it prompted him to keep talking. She drank some more of the terrible liquid, but found her mind wandering.

These people… they each had lives, families, loves, dreams. Some slumped at their boxes, lonely, while others laughed with friends. Some kept their clothing, poor though it was, reasonably clean—others were stained with crem and lavis ale. Several of them reminded her of Tyn, the way they talked with confidence, the way their interactions were a subtle game of one-upping each other.

Jor paused, as if expecting something from her. What… what had he been saying? Following him was getting harder, as her mind drifted.

“Go on,” she said.

He smiled, and launched into another story.

I’m not going to be able to imitate this, she thought, leaning against her box, until I’ve lived it. No more than I could draw their lives without having walked among them.

The barkeep came back with the bottle, and Shallan nodded. That last cup hadn’t burned nearly as much as the others.

“You… sure you want more?” the bouncer asked.

Storms… she was starting to feel really sick. She’d had four cups, yes, but they were little cups. She blinked, and turned.

The room spun in a blur, and she groaned, resting her head on the table.

Beside her, the bouncer sighed.

“I could have told you that you were wasting your time, Jor,” the barkeep said. “This one will be out before the hour is done. Wonder what she’s trying to forget…”

“She’s just enjoying a little free time,” Jor said.

“Sure, sure. With eyes like those? I’m sure that’s it.” The barkeep moved away.

“Hey,” Jor said, nudging Shallan. “Where are you staying? I’ll call you a palanquin to cart you home. You awake? You should get going before things go too late. I know some porters who can be trusted.”

“It’s… not even late yet…” Shallan mumbled.

“Late enough,” Jor said. “This place can get dangerous.”

“Yeaaah?” Shallan asked, a glimmer of memory waking inside of her. “People get stabbed?”

“Unfortunately,” Jor said.

“You know of some… ?”

“Never happens here in this area, at least not yet.”

“Where? So I… so I can stay away…” Shallan said.

“All’s Alley,” he said. “Keep away from there. Someone got stabbed behind one of the taverns just last night there. They found him dead.”

“Real… real strange, eh?” Shallan asked.

“Yeah. You heard?” Jor shivered.

Shallan stood up to go, but the room upended about her, and she found herself slipping down beside her stool. Jor tried to catch her, but she hit the ground with a thump, knocking her elbow against the stone floor. She immediately sucked in a little Stormlight to help with the pain.

The cloud around her mind puffed away, and her vision stopped spinning. In a striking moment, her drunkenness simply vanished.

She blinked. Wow. She stood up without Jor’s help, dusting off her coat and then pulling her hair back away from her face. “Thanks,” she said, “but that’s exactly the information I need. Barkeep, we settled?”

The woman turned, then froze, staring at Shallan, pouring liquid into a cup until it overflowed.

Shallan picked up her cup, then turned it and shook the last drop into her mouth. “That’s good stuff,” she noted. “Thanks for the conversation, Jor.” She set a sphere on the boxes as a tip, pulled on her hat, then patted Jor fondly on the cheek before striding out of the tent.